Divide and conquer

Published:

Donald Knuth, is a professor emeritus at Stanford University in Computer Science. In text, he wrote one of the most influential series of books called The Art of Computer Programming. While he was writing those books, he discovered typography and text layout and wrote TeX, the “word processing” system that many computer scientists, mathematicians, and engineers use for their writings — though I, like many others, use a simplified version of it called LaTeX.

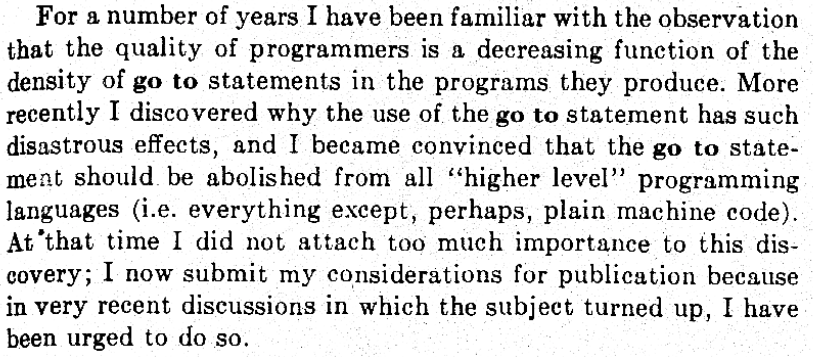

One of Knuth’s most influential papers is Structured Programming With Go To Statements, which was partially in response to Dijkstra’s Goto Statements Considered Harmful Dijkstra’s comment, in the first paragraph of the paper shown below, proposes that “higher level” languages should not include a goto statement.

Knuth’s paper is long, but he directly targets his unease with Dijkstra’s paper in this paragraph below.

Optimization?

I started writing this piece by wanting to talk about analysis of algorithms and why we should do it. As is usual with my contrarian streak, the first quote that came to mind was Knuth’s from the paper linked to above:

We should forget about small efficiencies, say about 97% of

the time: premature optimization is the root of all evil.

Does this mean we shouldn’t think about how well algorithms run at all?

No

Fairly obviously, my answer is no, because I’m teaching about how to analyze performance of data structures. The reason the answer is no is that while premature optimization is evil (or at least up to no good), mature reflection about the problem at hand isn’t.

The simplest way to make things more efficient (or effective) is the well-known strategy of divide and conquer. In computing, this often means taking a problem that needs to be solved for N items, splitting the N items into two groups of N/2 items. A quick example of this is a simple binary search versus a linear search.

Divide and conquer : binary searching

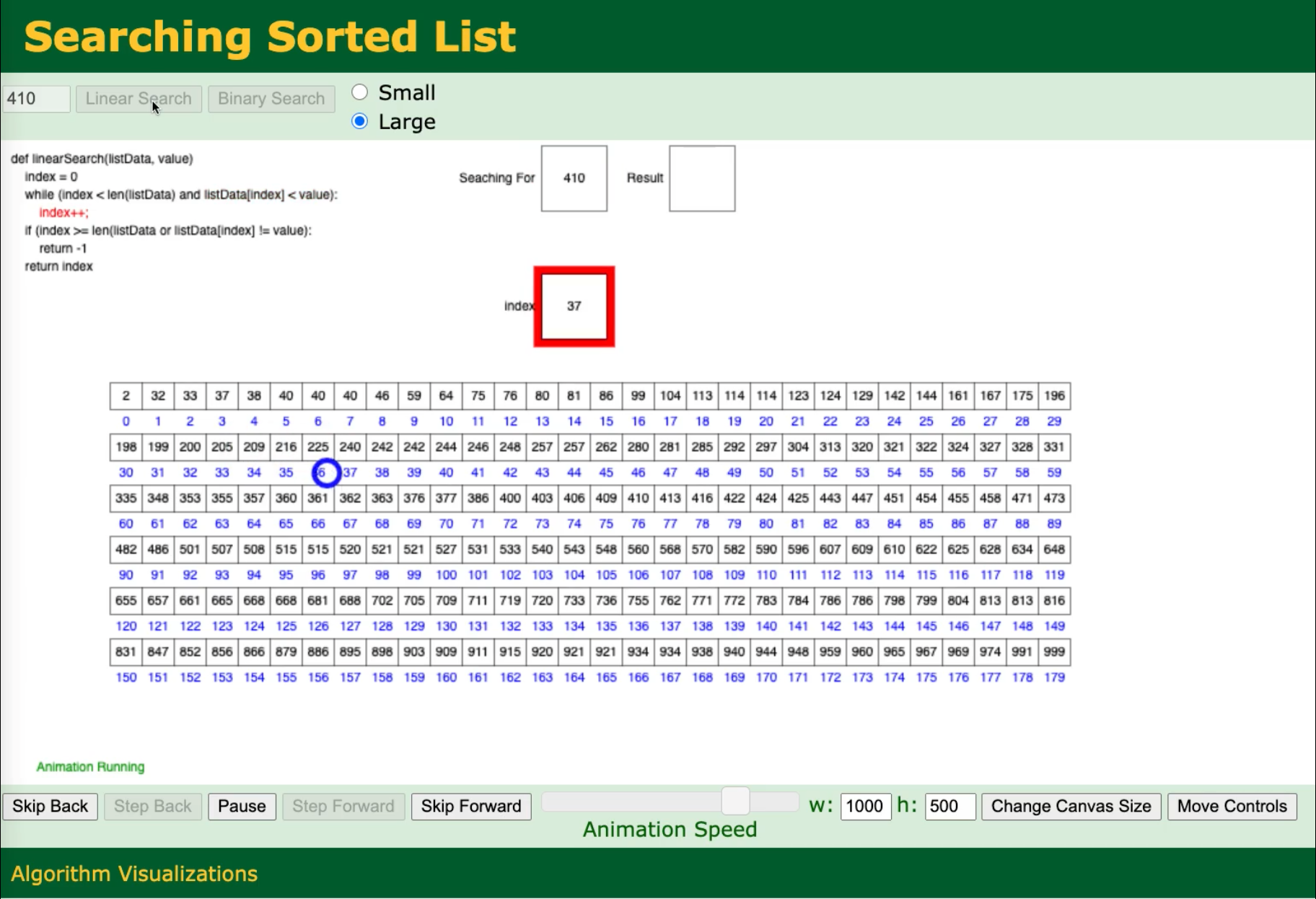

The the image below links to a video that I made of David Galles’s page linked above. It compares the linear search for the element 410 versus the binary search version in an ordered list.

As I hope you can see, the linear search approach is much slower than the binary search approach.

Here the linear approach will be O(N) for N elements in the array: in the worst case, we have to go through all N elements to get there. We could use this approach even if the list were unordered, and it would take the same amount of time / iterations.

The binary search approach uses the fact that the array is already sorted and samples each half of the array to see where it should look next. In this case, the binary search approach will take O(log2(N)) iterations.

Divide and conquer : sorting

The example above assumes that the array is already sorted. So, the question then is: how does one sort an array?

One answer is the bubble sort. In this approach, we move through the array comparing elements pairwise. If the pair is not in the order we want, we swap them. This is illustrated below.

An animation of the bubble sort algorithm done by Wikipedia user swfung8 under the creative commons share alike license.

This sorting technique is not very efficient. If we look at the average or worst cases, we’ll see that the algorithm is O(N2).

By using a divide-and-conquer approach, it’s possible to much better: O(N log2(N)).

There is a nice animation of several different sort techniques available here

Optimization!

Going back to Knuth’s statement, I hope you can see that not thinking about efficiency at all when programming can lead to selection of a very inefficient way of doing things. If we used a bubble sort for 1,024 items, that scales to O(1,048,576). For the same problem, using a binary tree approach can mean only O(10,240), or one hundred times fewer operations.

And that’s why we study data structures: to avoid making costly mistakes before we program.